#include <threads.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

thread_local int counter = 0;

int thread_func(void *arg) {

int id = *(int*)arg;

counter++; // Each thread increments its own copy

printf("Thread %d: counter = %d\n", id, counter);

return 0;

}

int main() {

thrd_t threads[4];

int ids[4] = {1, 2, 3, 4};

for (int i = 0; i < 4; i++) {

thrd_create(&threads[i], thread_func, &ids[i]);

}

for (int i = 0; i < 4; i++) {

thrd_join(threads[i], NULL);

}

printf("Main thread counter: %d\n", counter); // Main's own copy

return 0;

}Blog

Generic update

02 March 2026

A lot has changed since last update… The operating system now has:

-

working userspace shell along with various utility commands

-

mailing IPC system

-

PS/2 keyboard driver

-

graphical terminal

-

FAT16/32 drivers

There were a lot of changes made sort of at one moment, so that’s why I haven’t blogged about them. To have a shell you’d need a terminal driver, to type commands - a keyboard driver and to glue all of this together - an IPC mechanism of some sort. Just to get to a working shell you need to cover a lot of OSDev areas at once, which wouldn’t IMO make for a good read.

Right now my goal is to implement more shell commands, which still unfortunately won’t make for an interesting article. It’s mostly just busy work - add a "file delete" command, add a "directory create" command and so on. Nothing innovative nor worth talking about.

One thing may be interesting though regarding the shell. It would be a "find/search" command with grep-like functionality or perhaps a regex engine (?). This would actually involve some true algorithm work and thus allow me to farm more content.

Another thing on my list is to port a (real) programming interpreter - so far wren and berry have been decent cadidates, but we’ll see. I want to keep the shell more of a command prompt, rather than someting programmable with ifs and fors. I generall dislike bash/unix shell - it allows for some truly unhinged programming, which shouldn’t be the role of such tool. Leave programming to programming languages and basic commands to shells.

To conclude: I’m locked in now and not in a mood for writing this poetry, yet I still feel like I have to. I have to, so I don’t lose form and so that maybe the two people in the entire world have something cool to read.

See you in the next post!

Running my kernel on real hardware

08 February 2026

Developing a custom operating system is notoriously difficult. These days we have awesome developer tools such as QEMU or Bochs. Despite that, those tools can sometimes turn out to be faulty or simply not show the entire truth about the running OS - especially QEMU, which while works, is a little too loose and allows for some correctness issues to slip in (in regards to CPU features, stack alignment, device drivers and so on). Because of that, it’s very important to test once in a while on real hardware - the code MUST be correct for it to work.

At the end I’ll tell a short and funny story about my personal experience with QEMU ;).

In search for the right hardware

Of course we’re talking about x86/PC machines here

The right hardware will be either very easy or really difficult to buy depending on what platform you’re developing for.

If your OS is 32 bit (ie. runs on i386-based machines) then you’ve got a problem. 32 bit machines are hard to get these days and are quite expensive due to their high collector value and vintage/retro freaks willing to overpay for this electronic scrap. I myself own 2 32 bit intel machines - Pentium S and the OG i386DX, but they barely work and I doubt they could handle constantly smashing the reset button and rebooting.

64 bit machines are more modern (duh!) and thus you get a lot of quality-of-life features like USB booting, which is miles better than writing floppies or CD disks, just to find out your kernel doesn’t work and discard them, producing a mound of plastic garbage in the process.

Just because a machine is 64 bit, it doesn’t make it better for development! A CPU is not everything, it is rather just one of many puzzle pieces, which make up the entirety of the PC. This is why you have to mind what peripherals your machine offers. A lot of modern PCs don’t have legacy PS/2 ports or a serial port - and you can forget about LPT (rip). Everything is USB these days, which means that to have some simple debug printing (or just any output for that matter) you will need a graphics driver or a USB driver to send data. As you can imagine, this is really difficult to have when your OS is taking it’s baby steps, while a serial PC driver is like 30 lines of code. That’s why it’s important to have these simple, primitive, yet super useful peripherals available.

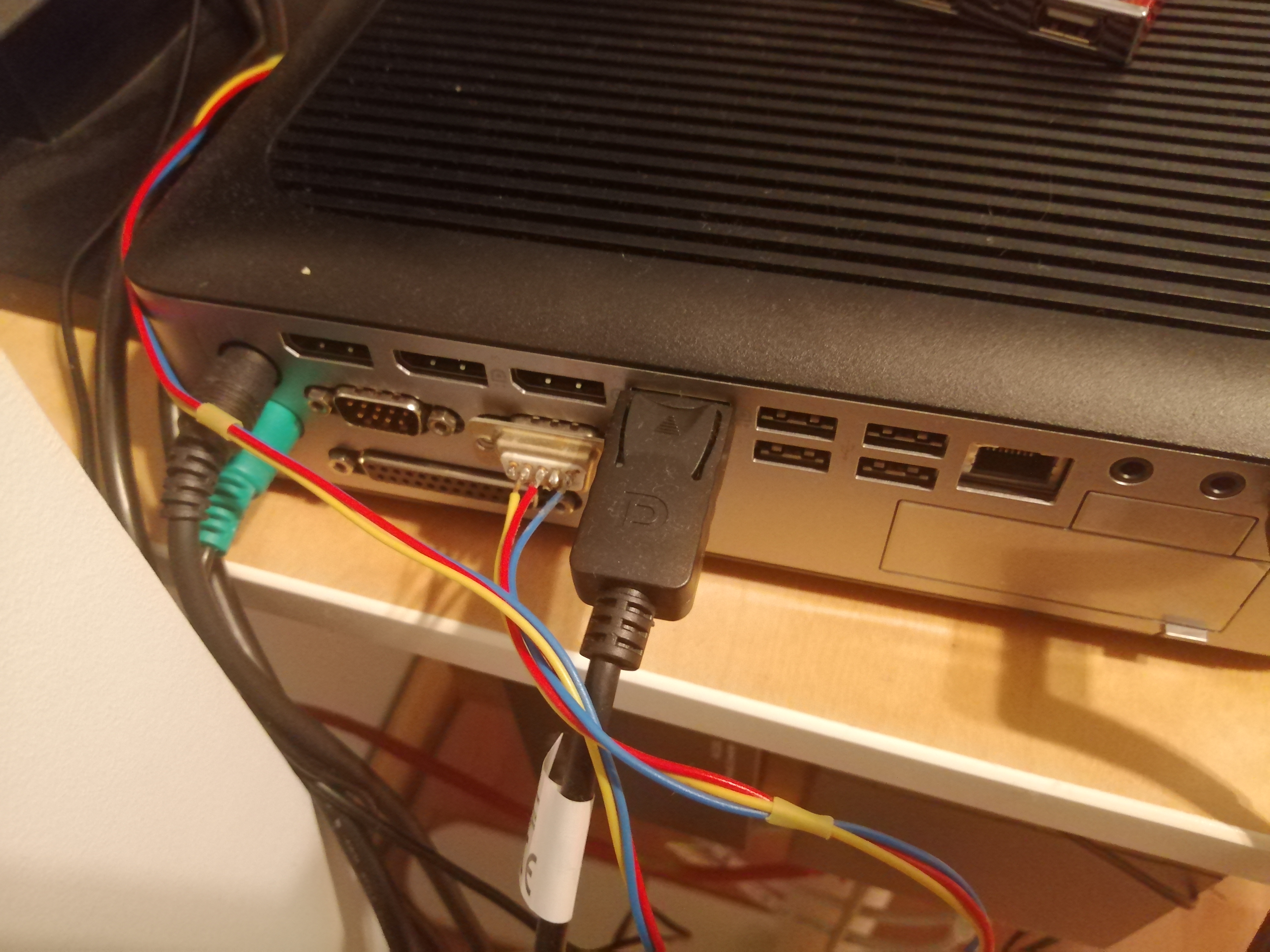

HP Thin Client T730

This is my machine of choice for this project. It’s 64 bit, has all the cool legacy peripherals (a serial port most importantly) and is very small/light. As you can see it easily fits on my table and doesn’t require too much space. Also a big plus is that if I get bored of OS dev eventually, I can use it as a secondary node in my home cloud infra.

Specs include:

-

32 GB hard drive; I can mount it out and use a bigger SSD, but I don’t need to for now

-

AMD RX-427BB

-

8 GB of RAM

-

2 serial ports

-

LPT port

-

PS/2 mouse and keyboard

Overall this mini PC is a big steal! It was only ~ 250 PLN or ~ 70 USD!

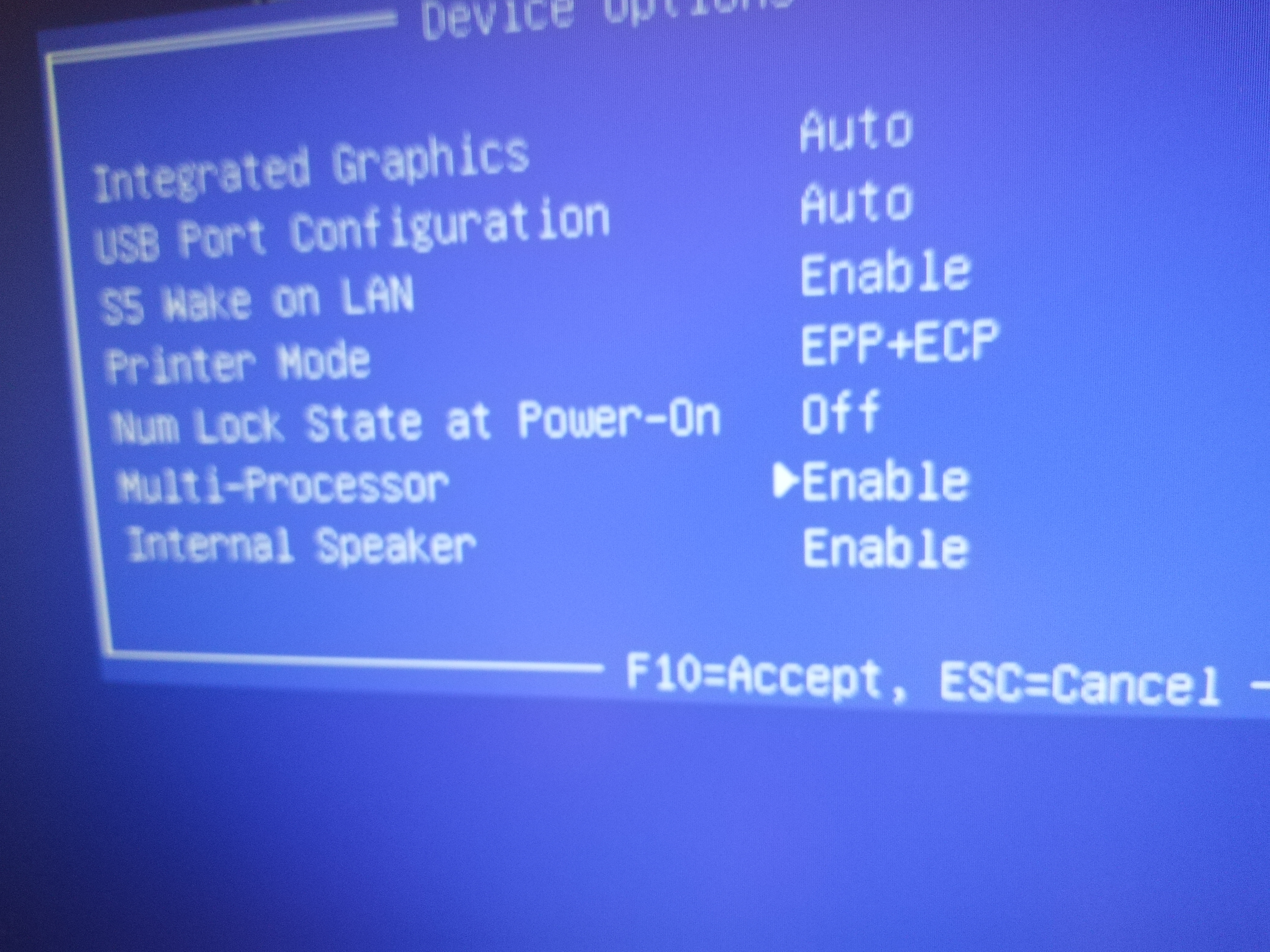

Also this BIOS feature is really important to me - multiprocessor or SMP support on/off. This is amazing for testing the correctness of SMP code, both in single core and multi core environment. May seem like a basic thing, but actually not many BIOSes support this.

Showcase

Implementing TLS (Thread Local storage) for x86_64

31 January 2026

In this article I’d like to explore the implementation details of thread local storage on x86_64/amd64 for my operating system with compliance to System V ABI.

full code is as always at: https://git.kamkow1lair.pl/kamkow1/MOP3

Preface

We’re going to implement the bare working minimum of the ABI, just enough to make thread

keyword work in Clang and GCC. The spec is more complicated than that. We’re going to implement static

TLS (there’s also dynamic TLS, you can look up tls_get_addr if you’re interested in going further).

Also I’d like to share this article as a very useful resource regarding the TLS: https://maskray.me/blog/2021-02-14-all-about-thread-local-storage. It’s more generally about TLS, but made for a great learning resource for me and I really recommend you read it too.

Other resources:

-

Spec reference: https://uclibc.org/docs/tls.pdf

-

OSDev Wiki: https://wiki.osdev.org/Thread_Local_Storage

What is thread local storage?

Thread local storage is a type of storage in a multitasked application, where each task has it’s own copy of it, distinct from other tasks.

Although the application is accessing and modifying a global variable, it’s actually different memories being used under the hood. Each thread has it’s own copy to work with.

What is thread_local? In the pre-C23 world it’s a macro, which expands to the _Thread_local keyword, which

is the same as compiler specific __thread in GCC and Clang.

Reverse engineering

We’re going to learn how the TLS works via reverse engineering. We need to understand it, before getting to Implementing it ourselves. Let’s look at the disassembly first, generated by Clang 21.1.0 on https://godbolt.org.

I’ve added some comments here, so everything is nice and easy to read.

/* int thread_func(void *arg) */

thread_func:

/* Push new stack frame */

push rbp

mov rbp, rsp

mov qword ptr [rbp - 8], rdi /* store arg on the stack frame */

/* Read the ID value */

/* int id = *(int*)arg; */

mov rax, qword ptr [rbp - 8]

mov eax, dword ptr [rax]

mov dword ptr [rbp - 12], eax

/* counter++; */

mov rax, qword ptr fs:[0] /* ?????????? */

lea rax, [rax + counter@TPOFF]

mov ecx, dword ptr [rax]

add ecx, 1 /* do the ++ */

mov dword ptr [rax], ecx

/* return 0; */

xor eax, eax

pop rbp

ret

/* The rest is irrelevant here... */

counter:

.long 0What is fs:[0] (also written commonly as %fs:0 in GNU syntax)?

We’re going to refer to fs as %fs (GNU syntax), because that’s how I write my assembly, but you can look

up the analogous syntax for you assembler (like nasm or fasm).

x86 segmentation

%fs is an x86 segment register. There are also other segment registers:

-

%cscode segment -

%dsdata segment -

%ssstack segment -

%esextra segment -

%fs,%gsgeneral segments

Real mode (16 bit)

x86_64 (yes, a 64 bit CPU) boots up first in 16 bit mode or the "real mode". In real mode we only have 16 bit registers, so one might think that we can address only up to 64K of memory. Segmentation let’s us use more memory, because it changes the logical addressing scheme. Instead of pointing to a specific byte in memory, we an point to a block of memory and displace from the base of it to get the byte - and thus we can address more than 64K. Early x86 CPUs (like the OG Intel 8086) could address up to 1MB.

This explains the %fs:0 syntax. We have a %fs base and a 0 displacement.

A good explaination can be also found on the OSDev wiki: https://wiki.osdev.org/Segmentation.

Also reading the GDT article will come in handy: https://wiki.osdev.org/Global_Descriptor_Table. From now on

I will assume we’re already working with 64 bit GDT and we’re going to skip the 32 bit mode entirely in this

article.

Long mode (64 bit)

Real mode uses 16 bit addresses as the segment base, so analogously 64 bit segmentation will use 64 bit addresses.

Segment registers are different

Segment registers are not like your typical %rax or %rcx - at least some. You can freely write to %ds,

%ss, %es and that’s it! %cs, %fs, %gs are special in that they cannot be written to manually.

%cs can be reloaded by for example lretq instruction, %fs and %gs require writing to an MSR

(will explain in a bit).

Detour about MSRs

MSR mean Model-Specific Register. Intel basically wanted to add unstable features and didn’t want to clutter up their architecture with experimental slop. Some of the MSRs were useful enough that they made it into future Intel CPUs and stayed with us. Generaly speaking, MSRs control OS-related stuff about the CPU.

MSRs are used with the rdmsr/wrmsr instructions. The scheme is like so:

movl NUMBER_OF_MSR, %ecx

movl VALUE_BITS_LOW, %eax

movl VALUE_BITS_HIGH, %edx

wrmsr

movl NUMBER_OF_MSR, %ecx

rdmsr

/* now %eax contains high bits and %edx low bits. These two shall be concatinated into a 64 bit value */%fs and MSRs

I’ve mentioned previously that the %fs and %gs registers can be written to by writing to an MSR - but which one?

The MSR we care about is called (in the Intel manual) IA32_FS_BASE. To address the confusion early on I’ll say

that some people call it slightly differently, for eg. in the Xen hypervisor code it’s called MSR_FS_BASE. My

kernel takes the definition header from Xen, so that’s why I will use Xen’s naming scheme, but IA32_FS_BASE

would be the official name.

Looking at the file kernel/amd64/msr-index.h we can see a juicy #define:

#define MSR_FS_BASE _AC (0xc0000100, U) /* 64bit FS base */The magic MSR number is 0xc0000100. Here’s how I’m using it:

void do_sched (struct proc* proc, spin_lock_t* cpu_lock, spin_lock_ctx_t* ctxcpu) {

spin_lock_ctx_t ctxpr;

spin_lock (&proc->lock, &ctxpr);

thiscpu->tss.rsp0 = proc->pdata.kernel_stack; /* set TSS kernel stack */

thiscpu->syscall_kernel_stack = proc->pdata.kernel_stack; /* set syscall entry stack */

amd64_wrmsr (MSR_FS_BASE, proc->pdata.fs_base); /* switch to proc's fs base */

spin_unlock (&proc->lock, &ctxpr);

spin_unlock (cpu_lock, ctxcpu);

amd64_do_sched ((void*)&proc->pdata.regs, (void*)proc->procgroup->pd.cr3_paddr);

}The MSR helpers are written like so:

/// Read a model-specific register

uint64_t amd64_rdmsr (uint32_t msr) {

uint32_t low, high;

__asm__ volatile ("rdmsr" : "=a"(low), "=d"(high) : "c"(msr));

return ((uint64_t)high << 32 | (uint64_t)low);

}

/// Write a model-specific register

void amd64_wrmsr (uint32_t msr, uint64_t value) {

uint32_t low = (uint32_t)(value & 0xFFFFFFFF);

uint32_t high = (uint32_t)(value >> 32);

__asm__ volatile ("wrmsr" ::"c"(msr), "a"(low), "d"(high));

}What we do is we swap out base value of %fs for each process and every process has it’s own TLS!

When processes are switched, the new MSR_FS_BASE is written.

So what is %fs:0 again?

We’ve managed to establish what %fs is, but what %fs:0 is?

The authors of System V TLS ABI for x86_64 were quite smart. %fs CANNOT be accessed on it’s own, sort of. We

can’t use it like a regular pointer to the TLS. We can only use segment registers with a displacement.

So when we can’t use %fs, we can use %fs:0! %fs points to the TLS + 8 byte pointer back to itself, so then

%fs:0 can become a pointer to the real TLS memory block.

Also, the TLS variable offsets are negative!

The TLS memory:

Var 1 Var 2 Var 3 Var 4 .... The pointer

+-------------------------------------------------------------------------------+

| | | | | | | | | | <---+

+-------------------------------------------------------------------------------+ |

|

^ |

| |

TLS (fs base) |

|

%fs:0 --------------+If this is too difficult to grasp (don’t worry, I’ve spent days banging by head against a wall mysekf), I’ll show you now the code, which handles the TLS in a bit. Now we’re going to take another detour to discuss how the TLS looks like from the perspective of the ELF file format.

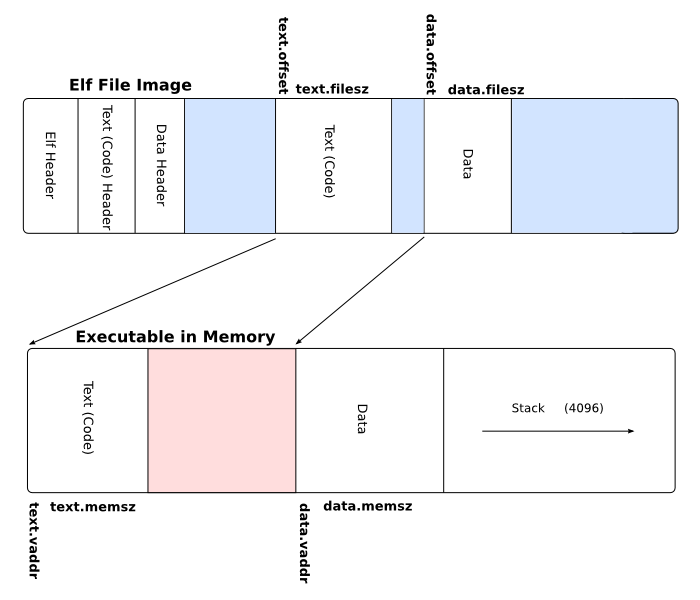

TLS and ELF relationship

I’m not going to go out of my way to explain the ELF format entirely - it’s out of scope for today, but I’ll link a useful article here: https://wiki.osdev.org/ELF. It’s a great read on the basics of the ELF format.

ELF has the so-called "sections". A section is a piece of data that makes up the final executable. A section can

be .text where your executable code resides or .rodata where your read-only data sits (like string literals).

ELF also has a special TLS section. This may seem confusing, since why would ELF store some sort of TLS, when each task must have it’s own? The TLS section is actually a template/"meta" section. It’s not the actual TLS, but rather a template of how should the TLS be contructed.

For example:

__thread int a = 123;

void my_thread (void) {

printf ("a = %d\n", a);

a = 456;

printf ("a = %d\n", a);

}The first printf will display 123, because the TLS template says that a shall have initial value of 123, but

then the thread is free to modify it’s own version. It just starts out with what is provided by the ELF file.

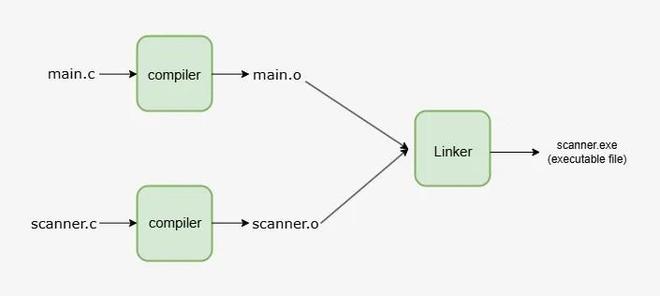

Linking the user application

An ELF application has to be linked after we’ve compiled all the necessary object files.

To get the exact ELF layout we need (remember, we’re making our own OS), we can use a linker script.

OUTPUT_FORMAT(elf64-x86-64)

ENTRY(_start)

PHDRS {

text PT_LOAD;

rodata PT_LOAD;

data PT_LOAD;

bss PT_LOAD;

tls PT_TLS; /* <------ !!!! */

}

SECTIONS {

. = 0x0000500000000000;

/* The executable code instructions */

.text : {

*(.text .text.*)

*(.ltext .ltext.*)

} :text

. = ALIGN(0x1000);

/* Read-only data */

.rodata : {

*(.rodata .rodata.*)

} :rodata

. = ALIGN(0x1000);

/* initialized data */

.data : {

*(.data .data.*)

*(.ldata .ldata.*)

} :data

. = ALIGN(0x1000);

__bss_start = .;

/* uninitialized data */

.bss : {

*(.bss .bss.*)

*(.lbss .lbss.*)

} :bss

__bss_end = .;

. = ALIGN(0x1000);

__tdata_start = .;

/* initialized TLS data */

.tdata : {

*(.tdata .tdata.*)

} :tls /* <------ !!!! */

__tdata_end = .;

__tbss_start = .;

/* uninitialized TLS data */

.tbss : {

*(.tbss .tbss.*)

} :tls /* <------ !!!! */

__tbss_end = .;

__tls_size = __tbss_end - __tdata_start;

/DISCARD/ : {

*(.eh_frame*)

*(.note .note.*)

}

}PT_TLS is the "program header" type - in this case we say that we want this part of the executable to be of

TLS type. This will help our OS' loader distinguish between different parts of the app and how should it act upon

them.

Also note that we mark .tdata and .tbss both as :tls. This just tells the linker to merge those sections

together into a tls section (which we mark as PT_TLS).

Loader

Now let’s take a look inside the ELF loader:

case PT_TLS: {

#if defined(__x86_64__)

if (phdr->p_memsz > 0) {

/* What is the aligment we need to use? */

size_t tls_align = phdr->p_align ? phdr->p_align : sizeof (uintptr_t);

/* Size of the TLS memory block (variables go here) */

size_t tls_size = align_up (phdr->p_memsz, tls_align);

/* Size needed - TLS block size + 8 bytes (64 bits) for back pointer */

size_t tls_total_needed = tls_size + sizeof (uintptr_t);

/* amount of pages to allocate */

size_t blks = div_align_up (tls_total_needed, PAGE_SIZE);

/* Initialize TLS template in the procgroup. This will be copied into individual TLSes */

proc->procgroup->tls.tls_tmpl_pages = blks;

proc->procgroup->tls.tls_tmpl_size = tls_size;

proc->procgroup->tls.tls_tmpl_total_size = tls_total_needed;

/* malloc () and zero out */

proc->procgroup->tls.tls_tmpl = malloc (blks * PAGE_SIZE);

memset (proc->procgroup->tls.tls_tmpl, 0, blks * PAGE_SIZE);

/* copy initialized stuff */

memcpy (proc->procgroup->tls.tls_tmpl, (void*)((uintptr_t)elf + phdr->p_offset),

phdr->p_filesz);

proc_init_tls (proc);

}

#endif

} break;void proc_init_tls (struct proc* proc) {

struct limine_hhdm_response* hhdm = limine_hhdm_request.response;

/* This application doesn't use TLS */

if (proc->procgroup->tls.tls_tmpl == NULL)

return;

size_t tls_size = proc->procgroup->tls.tls_tmpl_size;

size_t pages = proc->procgroup->tls.tls_tmpl_pages;

uintptr_t tls_paddr;

uint32_t flags = MM_PG_USER | MM_PG_PRESENT | MM_PG_RW;

/* allocate a new TLS memory space and map it into the procgroup's address space */

uintptr_t tls_vaddr = procgroup_map (proc->procgroup, 0, pages, flags, &tls_paddr);

uintptr_t k_tls_addr = (uintptr_t)hhdm->offset + tls_paddr;

/* zero and copy the template contents */

memset ((void*)k_tls_addr, 0, pages * PAGE_SIZE);

memcpy ((void*)k_tls_addr, (void*)proc->procgroup->tls.tls_tmpl, tls_size);

/* kernel address and user address + size will point to the tls pointer */

uintptr_t ktcb = k_tls_addr + tls_size;

uintptr_t utcb = tls_vaddr + tls_size;

/* write the pointer value, which makes the TLS point to itself */

*(uintptr_t*)ktcb = utcb;

/* store as fs_base for switching during scheduling */

proc->pdata.fs_base = utcb;

/* save allocation address to later free it when not needed */

proc->pdata.tls_vaddr = tls_vaddr;

}Conclusion

And that’s it! we can use the TLS now in user apps!

#define MUTEX 2000

LOCAL volatile char letter = 'c';

void app_proc1 (void) {

letter = 'a';

for (;;) {

mutex_lock (MUTEX);

for (int i = 0; i < 3; i++)

test (letter);

mutex_unlock (MUTEX);

}

process_quit ();

}

void app_proc2 (void) {

letter = 'b';

for (;;) {

mutex_lock (MUTEX);

for (int i = 0; i < 3; i++)

test (letter);

mutex_unlock (MUTEX);

}

process_quit ();

}

void app_proc3 (void) {

letter = 'c';

for (;;) {

mutex_lock (MUTEX);

for (int i = 0; i < 3; i++)

test (letter);

mutex_unlock (MUTEX);

}

process_quit ();

}

void app_main (void) {

mutex_create (MUTEX);

letter = 'a';

process_spawn (&app_proc1, NULL);

process_spawn (&app_proc2, NULL);

process_spawn (&app_proc3, NULL);

for (;;) {

mutex_lock (MUTEX);

for (int i = 0; i < 3; i++)

test (letter);

mutex_unlock (MUTEX);

}

}My personal thoughts

This was difficult… Way too difficult to implement. When reading the spec and then trying to make it work, I’ve noticed that all this pointer/size/alignment trickery is just so we can go around the face that x86_64 doesn’t have a built-in architectural mechanism to support such thing as TLS. All you have is a bunch of free registers and it’s up to you to make something out of that. I guess ARM is better in this case, because there’s a single source of authority that produces the CPU and sets the rules to abide by.

Mutexes and process suspension in kernels

30 January 2026

Hello!

In this blog post I would like to share my thoughts and some implementation details about the mutex mechanism in MOP3!

WAIT! MOP 3?

Yes! MOP2 is undergoing a huge rewrite and redesign right now, due to me not being happy with some design choices of the system. This is mostly about writing SMP-first/SMP-friendly code. The rewrite turned out to be so big that it was just easier to start a new project, while reusing big portions of older MOP2 code - and thus MOP3 was born. Excpect more interesting updates in the future!

New GIT repository: https://git.kamkow1lair.pl/kamkow1/MOP3

Multitasking is deliquete

Preface

This portion of the article will explain critical sections and why they’re so fragile. If you’re an advanced reader, you can easily skip it.

Writing multitasked/paralell code is notoriously difficult and can lead to bazzire, awful and undeterministic

bugs. One should keep in mind that multitasked code is not something debuggable with normal developer tools

like gdb or lldb or some other crash analyzers and code inspectors. Rather than that, such code should be

proven to be safe/correct, either by just reading the code or writing formal proofs.

Formal proofs can be written using the Promela scripting language: https://spinroot.com/spin/whatispin.html

The problem

Imagine this problem in a multitasked application:

struct my_list_node {

struct my_list_node* next, *prev;

int value;

};

/* These are complex operations on multiple pointers */

#define LIST_ADD(list, x) ...

#define LIST_REMOVE(list, x) ...

struct my_list_node* my_list = ...;

void thread_A (void) {

struct my_list_node* new_node = malloc (sizeof (*new_node));

new_node->value = 67;

LIST_ADD (my_list, new_node);

}

void thread_B (void) {

LIST_REMOVE (my_list, my_list); /* remove head */

}The issue here is that, while thread_A is adding a new node, thread_B can try to remove it. This will

lead to pointer corruption, since LIST_REMOVE and LIST_ADD will try to re-link list’s nodes at the same

time.

Such fragile sections of code are called "critical sections", meaning that one has to be VERY careful when tasks enter it. So where are they in the code?

void thread_A (void) {

/* NOT CRITICAL - new_node is not yet visible to other tasks */

struct my_list_node* new_node = malloc (sizeof (*new_node));

new_node->value = 67;

/* CRITICAL */

LIST_ADD (my_list, new_node);

}

void thread_B (void) {

/* CRITICAL */

LIST_REMOVE (my_list, my_list); /* remove head */

}So how do we solve this?

This specific problem can be easily solved by, what’s called "Mutual Exclusion" or "MutEx" for short.

Why "mutual exclusion"? As you can see, to modify the list, a task needs exclusive access to it, ie. nobody else can be using the list at the same time. Kind of like a bathroom - imagine someone happily walks in while you’re sitting on a toilet and tries to fit right beside you.

A poor man’s mutex and atomicity

Let’s park it here and move to a slightly different, but related topic - atomicity. What is it?

To be atomic is to be indivisible. An atomic read or a write is an operation that can’t be split up and has to be completed from start to finish without being interrupted.

While atomic operations are mutually exclusive, they work on a level of individual reads/writes of integers of various sizes. One can atomically read/write a byte or an uint64_t. This of course won’t solve our problem, because we’re operating on many integers (here pointers) simultaneously - struct my_list_node’s prev and next pointers - but despite that, we can leverage atomicity to implement higher level synchronization constructs.

BTW, documentation on atomic operations in C can be found here: https://en.cppreference.com/w/c/atomic.html. The functions/macros are implemented internally by the compiler, for eg. GCC atomics: https://gcc.gnu.org/onlinedocs/gcc/_005f_005fatomic-Builtins.html. They have to be implemented internally, because they’re very platform dependant and each architecture may handle atomicity slightly differently, although the same rules apply everwhere.

Now that we’ve discussed C atomics, let’s implement the poor man’s mutex!

What needs to be done? We’ve established that only one task can be using the list at a time. We’d probably want some sort of a flag to know if it’s our turn to use the list. If the flag is set, it means that someone is currently using the list and thus we have to wait. If clear, we’re good to go.

Obviously, the flag has to be atomic by itself. Otherwise one task could read the flag, while it’s being updated, leading to a thread entering the critical section, when it’s not it’s turn.

#include <stdatomic.h>

#define SPIN_LOCK_INIT ATOMIC_FLAG_INIT

typedef atomic_flag spin_lock_t;

void spin_lock (spin_lock_t* sl) {

while (atomic_flag_test_and_set_explicit (sl, memory_order_acquire))

;

}

void spin_unlock (spin_lock_t* sl) {

atomic_flag_clear_explicit (sl, memory_order_release);

}

// List same as before...

// the lock

spin_lock_t the_lock = SPIN_LOCK_INIT;

void thread_A (void) {

struct my_list_node* new_node = malloc (sizeof (*new_node));

new_node->value = 67;

spin_lock (&the_lock);

LIST_ADD (my_list, new_node);

spin_unlock (&the_lock);

}

void thread_B (void) {

spin_lock (&the_lock);

LIST_REMOVE (my_list, my_list); /* remove head */

spin_unlock (&the_lock);

}As you can see, if a task tries to modify the list, it must first check whether it can do so. If not, wait until such operation is possible. Pretty easy, eh?

There are some big and small improvements to be made, so let’s pick up a spying glass and analyze!

Small inefficiency

When we fail to lock the spin lock, we’re stuck in a spin-loop. This is really bad for performance, because we’re just eating up CPU cycles for nothing. A better spin lock would "relax the CPU", ie. tell the processor that it’s stuck in a spin-loop and make it consume less power or switch hardware tasks.

On x86 we have a pause instruction: https://www.felixcloutier.com/x86/pause.

ARM has a yield instruction: https://developer.arm.com/documentation/dui0802/b/A32-and-T32-Instructions/SEV—SEVL—WFE—WFI—and-YIELD.

Big inefficiency

Despite the pause or yield instructions and such, we still have an underlying flaw in our spin lock.

The issue is that we’re just spinning when we fail to acquire the lock, when we could hand over control

to another task - we can’t have access ourselves, so let someone else take the precious CPU time and get

a little bit of work done.

Despite this "inefficiency", spin locks are the most primitive-yet-useful way of locking. This example shows a simple solution to a simple problem, but in the real-world one would use spin locks to implement higher level/smarter ways of providing task synchronization.

The better mutex and it’s building blocks

So if spinning in place is "bad" for performance, what do we do then? Here come the "suspension queues".

Scheduler states

If we fail to acquire a mutex, it means that we’re stuck waiting for it. If we’re stuck, we shouldn’t be scheduled, ie. given CPU time (there’s no work to be done). To denote this, we have to introduce another process state:

/* process states */

#define PROC_READY 0

#define PROC_DEAD 1

#define PROC_SUSPENDED 2 /* NEW */This new state describes a new situation in our scheduler - a process IS alive, but CANNOT be scheduled. Before we only had alive (schedulable) processes and dead (unschedulable) processes.

Now our scheduler won’t pick up suspended processes:

// ...

static struct proc* proc_find_sched (struct cpu* cpu) {

if (!cpu->proc_run_q)

return NULL;

struct list_node_link *current, *start;

if (cpu->proc_current)

current = cpu->proc_current->cpu_run_q_link.next;

else

current = cpu->proc_run_q;

if (!current)

current = cpu->proc_run_q;

start = current;

do {

struct proc* proc = list_entry (current, struct proc, cpu_run_q_link);

if (atomic_load (&proc->state) == PROC_READY)

return proc;

current = current->next ? current->next : cpu->proc_run_q;

} while (current != start);

return NULL;

}

// ...

void proc_sched (void) {

spin_lock_ctx_t ctxcpu;

int s_cycles = atomic_fetch_add (&sched_cycles, 1);

if (s_cycles % SCHED_REAP_FREQ == 0)

proc_reap ();

struct proc* next = NULL;

struct cpu* cpu = thiscpu;

spin_lock (&cpu->lock, &ctxcpu);

next = proc_find_sched (cpu);

if (next) {

cpu->proc_current = next;

do_sched (next, &cpu->lock, &ctxcpu);

} else {

cpu->proc_current = NULL;

spin_unlock (&cpu->lock, &ctxcpu);

spin ();

}

}Suspension queues

A suspension queue is a little tricky - it’s not just a list of suspended processes. We need to establish a many:many relationship (kinda like in databases). A process can be a member of many suspension queues (image a process, which waits on many mutexes) and a single suspension queue has many member processes. In order to achieve that, we can do some pointer trickery!

struct proc {

int pid;

struct rb_node_link proc_tree_link;

struct rb_node_link procgroup_memb_tree_link;

struct list_node_link cpu_run_q_link;

struct list_node_link reap_link;

struct list_node_link* sq_entries; /* list of intermediate structs */

struct procgroup* procgroup;

struct proc_platformdata pdata;

uint32_t flags;

spin_lock_t lock;

struct cpu* cpu;

atomic_int state;

uintptr_t uvaddr_argument;

};

struct proc_suspension_q {

struct list_node_link* proc_list; /* list of processes via proc_sq_entry */

spin_lock_t lock;

};

/* the intermediate struct */

struct proc_sq_entry {

struct list_node_link sq_link; /* list link */

struct list_node_link proc_link; /* list link */

struct proc* proc; /* pointer back to the process */

struct proc_suspension_q* sq; /* pointer back to the suspension queue */

};Now we can talk about the suspend/resume algorithms.

bool proc_sq_suspend (struct proc* proc, struct proc_suspension_q* sq, spin_lock_t* resource_lock,

spin_lock_ctx_t* ctxrl) {

spin_lock_ctx_t ctxpr, ctxcpu, ctxsq;

struct cpu* cpu = proc->cpu;

/* allocate intermediate struct */

struct proc_sq_entry* sq_entry = malloc (sizeof (*sq_entry));

if (!sq_entry) {

spin_unlock (resource_lock, ctxrl);

return PROC_NO_RESCHEDULE;

}

/* set links on both ends */

sq_entry->proc = proc;

sq_entry->sq = sq;

/* lock with compliance to the lock hierachy */

spin_lock (&cpu->lock, &ctxcpu);

spin_lock (&proc->lock, &ctxpr);

spin_lock (&sq->lock, &ctxsq);

spin_unlock (resource_lock, ctxrl);

/* transition the state to PROC_SUSPENDED */

atomic_store (&proc->state, PROC_SUSPENDED);

/* append to sq's list */

list_append (sq->proc_list, &sq_entry->sq_link);

/* append to proc's list */

list_append (proc->sq_entries, &sq_entry->proc_link);

/* remove from CPU's run list and decrement CPU load counter */

list_remove (cpu->proc_run_q, &proc->cpu_run_q_link);

atomic_fetch_sub (&cpu->proc_run_q_count, 1);

if (cpu->proc_current == proc)

cpu->proc_current = NULL;

/* a process is now unschedulable, so it doesn't need a CPU */

proc->cpu = NULL;

/* release the locks */

spin_unlock (&sq->lock, &ctxsq);

spin_unlock (&proc->lock, &ctxpr);

spin_unlock (&cpu->lock, &ctxcpu);

return PROC_NEED_RESCHEDULE;

}

bool proc_sq_resume (struct proc* proc, struct proc_sq_entry* sq_entry) {

spin_lock_ctx_t ctxsq, ctxpr, ctxcpu;

struct cpu* cpu = cpu_find_lightest (); /* find the least-loaded CPU */

struct proc_suspension_q* sq = sq_entry->sq;

/* acquire necessary locks */

spin_lock (&cpu->lock, &ctxcpu);

spin_lock (&proc->lock, &ctxpr);

spin_lock (&sq->lock, &ctxsq);

/* remove from sq's list */

list_remove (sq->proc_list, &sq_entry->sq_link);

/* remove from proc's list */

list_remove (proc->sq_entries, &sq_entry->proc_link);

/* Give the CPU to the process */

proc->cpu = cpu;

/*

* update process state to PROC_READY, but only if it's not waiting inside

* another suspension queue.

*/

if (proc->sq_entries == NULL)

atomic_store (&proc->state, PROC_READY);

/* attach to CPU's run list and increment load counter */

list_append (cpu->proc_run_q, &proc->cpu_run_q_link);

atomic_fetch_add (&cpu->proc_run_q_count, 1);

/* unlock */

spin_unlock (&sq->lock, &ctxsq);

spin_unlock (&proc->lock, &ctxpr);

spin_unlock (&cpu->lock, &ctxcpu);

/* intermediate struct is no longer needed, so free it */

free (sq_entry);

return PROC_NEED_RESCHEDULE;

}As you can see, this algorithm is quite simple actually. It’s just a matter of safely appending/removing links to specific lists.

The mutex itself

The mutex is quite simple too.

struct proc_mutex {

struct proc_resource* resource; /* pointer back to the resource */

bool locked; /* taken or free */

struct proc_suspension_q suspension_q; /* suspension queue of waiting processes */

struct proc* owner; /* current owner of the mutex / process, which can enter the critical section */

};And now the lock and unlock algorithms.

bool proc_mutex_lock (struct proc* proc, struct proc_mutex* mutex) {

spin_lock_ctx_t ctxmt;

spin_lock (&mutex->resource->lock, &ctxmt);

/* we can enter if: the mutex is NOT locked or we're already the owner of the mutex */

if (!mutex->locked || mutex->owner == proc) {

mutex->locked = true;

mutex->owner = proc;

spin_unlock (&mutex->resource->lock, &ctxmt);

return PROC_NO_RESCHEDULE;

}

/* we failed to become an owner, thus we have to free up the CPU and suspend ourselves */

return proc_sq_suspend (proc, &mutex->suspension_q, &mutex->resource->lock, &ctxmt);

}

bool proc_mutex_unlock (struct proc* proc, struct proc_mutex* mutex) {

spin_lock_ctx_t ctxmt, ctxsq;

spin_lock (&mutex->resource->lock, &ctxmt);

/*

* we can't unlock a mutex, which we don't already own,

* otherwise we could just steal someone else's mutex.

*/

if (mutex->owner != proc) {

spin_unlock (&mutex->resource->lock, &ctxmt);

return PROC_NO_RESCHEDULE;

}

spin_lock (&mutex->suspension_q.lock, &ctxsq);

struct list_node_link* node = mutex->suspension_q.proc_list;

/*

* This is a little tricky. What we're doing here is "direct handoff" - we basically

* transfer ownership, while keeping the mutex locked, instead of just unlocking and

* resuming everyone.

*/

if (node) {

struct proc_sq_entry* sq_entry = list_entry (node, struct proc_sq_entry, sq_link);

struct proc* resumed_proc = sq_entry->proc;

/* transfer ownership */

mutex->owner = resumed_proc;

mutex->locked = true;

spin_unlock (&mutex->suspension_q.lock, &ctxsq);

spin_unlock (&mutex->resource->lock, &ctxmt);

/* resume new owner - it can enter the critical section now */

return proc_sq_resume (resumed_proc, sq_entry);

}

/* no possible future owner found, so we just unlock */

mutex->locked = false;

mutex->owner = NULL;

spin_unlock (&mutex->suspension_q.lock, &ctxsq);

spin_unlock (&mutex->resource->lock, &ctxmt);

return PROC_NEED_RESCHEDULE;

}Direct handoff and "The Thundering Herd"

Why the direct handoff? Why not just unlock the mutex?

The thundering herd problem is very common in multitasking and synchronization.

We free the mutex, wake up all waiters and now anyone can take it. The issue here is that ONLY ONE task will eventually get to acquire the mutex and enter the critical section. If only one gets to take the mutex, why bother waking up everyone? The solution here would be to pass down the ownership to the first encountered waiter and then the next one and so on. Also waking everyone would be cause a performance penatly, because we’re wasting CPU cycles just to be told not to execute any further.

two birds, one stone

Via direct handoff, we’ve also just eliminated a fairness problem.

What does it mean for a mutex to be "fair"?

Fairness in synchronization means that each task at some point will get a chance to work in the critical section.

Fairness example problem:

#include <stdatomic.h>

#define SPIN_LOCK_INIT ATOMIC_FLAG_INIT

typedef atomic_flag spin_lock_t;

void spin_lock (spin_lock_t* sl) {

while (atomic_flag_test_and_set_explicit (sl, memory_order_acquire))

__asm__ volatile ("pause");

}

void spin_unlock (spin_lock_t* sl) {

atomic_flag_clear_explicit (sl, memory_order_release);

}

// the lock

spin_lock_t the_lock = SPIN_LOCK_INIT;

void thread_A (void) {

for (;;) {

spin_lock (&the_lock);

{

/* critical section goes here */

}

spin_unlock (&the_lock);

}

}

void thread_B (void) {

for (;;) {

spin_lock (&the_lock);

{

/* critical section goes here */

}

spin_unlock (&the_lock);

}

}Let’s take thread_B for example. thread_B locks, does it’s thing and unlocks. Because it’s in an infinite

loop, there’s a chance that it may re-lock too quickly, before thread_A gets the chance. This causes a

fairness issue, because thread_A is getting starved - it can’t enter the critical section, even though it

plays by the rules, synchronizing properly with thread_B via a spinlock. On real CPUs (ie. real hardware

or QEMU with -enable-kvm), there will always be some tiny delays/"clog ups" that mitigate this problem,

but theoretically it is possible that a task can starve.

Our algorithm solves this by always selecting the next thread to own the mutex, so we never get the issue that when we unlock, the new owner is selected randomly - the first one to get it, owns it. This makes the approach more deterministic/predictible.

Final result

This is the final result of our work!

#include <limits.h>

#include <proc/local.h>

#include <proc/proc.h>

#include <stddef.h>

#include <stdint.h>

#include <string/string.h>

/* ID of the mutex resource */

#define MUTEX 2000

/* TLS (thread-local storage) support was added recently ;)! */

LOCAL volatile char letter = 'x';

void app_proc (void) {

char arg_letter = (char)(uintptr_t)argument_ptr ();

letter = arg_letter;

for (;;) {

/* enter the critical section, print the _letter_ 3 times and leave */

mutex_lock (MUTEX);

for (int i = 0; i < 3; i++)

test (letter);

mutex_unlock (MUTEX);

}

process_quit ();

}

void app_main (void) {

mutex_create (MUTEX);

letter = 'a';

process_spawn (&app_proc, (void*)'b');

process_spawn (&app_proc, (void*)'c');

process_spawn (&app_proc, (void*)'d');

for (;;) {

mutex_lock (MUTEX);

for (int i = 0; i < 3; i++)

test (letter);

mutex_unlock (MUTEX);

}

}FAT filesystem integration into MOP2

19 November 2025

Hello, World!

I would like to present to you FAT filesystem integration into the MOP2 operating system! This was

possible thanks to fat_io_lib library by UltraEmbedded, because there’s no way I’m writing an

entire FAT driver from scratch ;).

Source for fat_io_lib: https://github.com/ultraembedded/fat_io_lib

Needed changes and a "contextual" system

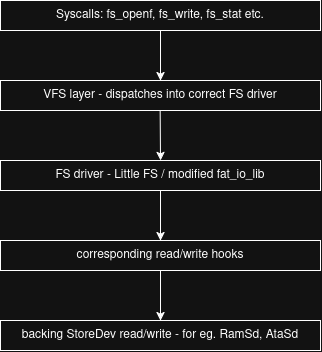

Integrating fat_io_lib wasn’t so straightforward as I thought it would be. To understand the problem we need to first understand the current design of MOP2’s VFS.

MOP2’s VFS explained

The VFS (ie. Virtual File System) is a Windows/DOS-style labeled VFS. Mountpoints are identified by

a label, like for eg. sys:/boot/mop2 or base:/scripts/mount.tb, which kinda looks like

C:\Path\To\File in Windows. I’ve chosen this style of VFS over the UNIX kind, because it makes more

sense to me personally. A mountpoint label can point to a physical device, a virtual device (ramsd)

or a subdevice/partition device. In the UNIX world on the other hand, we have a hierarchical VFS, so

paths look like /, /proc, /dev, etc. This is a little confusing to reason about, because you’d

think that if / is mounted let’s say on a drive sda0, then /home would be a home directory

within the root of that device. This is not always the case. / can be placed on sda0, but /home

can be placed on sdb0, so now something that looks like a subdirectory, is now a pointer to an

entirely different media. Kinda confusing, eh?

The problem

So now that we know how MOP2’s VFS works, let’s get into low-level implementation details. To handle mountpoints we use a basic hashtable. We just map the label to the proper underlying file system driver like so:

base -> Little FS

uhome -> Little FS

sys -> FAT16Through this table, we can see that we have two mountpoints (base and uhome), which both use Little FS, but are placed on different media entirely. Base is located on a ramsd, which is entirely virtual and uhome is a partition on a physical drive.

To manage such setup, we need to have separate filesystem library contexts for each mountpoint.

A context here means an object, which stores info like block size, media read/write/sync hooks,

media capacity and so on. Luckly, with Little FS we could do this out of the box, because it blesses

us with lfs_t - an instance object. We can then create this object for each Little FS mountpoint.

typedef struct VfsMountPoint {

int _hshtbstate;

char label[VFS_MOUNTPOINT_LABEL_MAX];

int32_t fstype;

StoreDev *backingsd;

VfsObj *(*open)(struct VfsMountPoint *vmp, const char *path, uint32_t flags);

int32_t (*cleanup)(struct VfsMountPoint *vmp);

int32_t (*stat)(struct VfsMountPoint *vmp, const char *path, FsStat *statbuf);

int32_t (*fetchdirent)(struct VfsMountPoint *vmp, const char *path, FsDirent *direntbuf, size_t idx);

int32_t (*mkdir)(struct VfsMountPoint *vmp, const char *path);

int32_t (*delete)(struct VfsMountPoint *vmp, const char *path);

// HERE: instance objects for the underlying filesystem driver library.

union {

LittleFs littlefs;

FatFs fatfs;

} fs;

SpinLock spinlock;

} VfsMountPoint;

typedef struct {

SpinLock spinlock;

VfsMountPoint mountpoints[VFS_MOUNTPOINTS_MAX];

} VfsTable;

// ...int32_t vfs_init_littlefs(VfsMountPoint *mp, bool format) {

// Configure Little FS

struct lfs_config *cfg = dlmalloc(sizeof(*cfg));

memset(cfg, 0, sizeof(*cfg));

cfg->context = mp;

cfg->read = &portlfs_read; // Our read/write hooks

cfg->prog = &portlfs_prog;

cfg->erase = &portlfs_erase;

cfg->sync = &portlfs_sync;

cfg->block_size = LITTLEFS_BLOCK_SIZE;

cfg->block_count = mp->backingsd->capacity(mp->backingsd) / LITTLEFS_BLOCK_SIZE;

// left out...

int err = lfs_mount(&mp->fs.littlefs.instance, cfg);

if (err < 0) {

ERR("vfs", "Little FS mount failed %d\n", err);

return E_MOUNTERR;

}

// VFS hooks

mp->cleanup = &littlefs_cleanup;

mp->open = &littlefs_open;

mp->stat = &littlefs_stat;

mp->fetchdirent = &littlefs_fetchdirent;

mp->mkdir = &littlefs_mkdir;

mp->delete = &littlefs_delete;

return E_OK;

}So where is the problem? It’s in the fat_io_lib library. You see, the creators of Little FS thought this out pretty well and designed their library in such manner that we can do cool stuff like this. The creators of fat_io_lib on the other hand… yeah. Here are the bits of internals of fat_io_lib:

//-----------------------------------------------------------------------------

// Locals

//-----------------------------------------------------------------------------

static FL_FILE _files[FATFS_MAX_OPEN_FILES];

static int _filelib_init = 0;

static int _filelib_valid = 0;

static struct fatfs _fs;

static struct fat_list _open_file_list;

static struct fat_list _free_file_list;There’s no concept of a "context" - everything is thrown into a bunch of global variables. To clarify: THIS IS NOT BAD! This is good if you need a FAT library for let’s say a microcontroller, or some other embedded device. Less code/stuff == less memory usage and so on.

When I was searching online for a FAT library, I wanted something like Little FS, but to my suprise there are no libraries for FAT designed like this? Unless it’s a homebrew OsDev project, of course. I’ve even went on reddit to ask and got nothing, but cricket noises ;(.

I’ve decided to modify fat_io_lib to suit my needs. I mean, most of the code is already written for me anyway, so I’m good.

The refactoring was quite easy to my suprise! The state of the library is global, but it’s all nicely placed in one spot, so we can then move it out into a struct:

struct fat_ctx {

FL_FILE _files[FATFS_MAX_OPEN_FILES];

int _filelib_init;

int _filelib_valid;

struct fatfs _fs;

struct fat_list _open_file_list;

struct fat_list _free_file_list;

void *extra; // we need this to store a ref to the mountpoint to access storage device hooks

};// This is what our VfsMountPoint struct from earlier was referencing, BTW.

typedef struct {

struct fat_ctx instance;

} FatFs;I’ve then gone on a compiler error hunt for about 2 hours! All I had to do is change references for

eg. from _fs.some_field into ctx→_fs.some_field. It was all pretty much brainless work - just

compile the code, read the error line number, edit the variable reference, repeat.

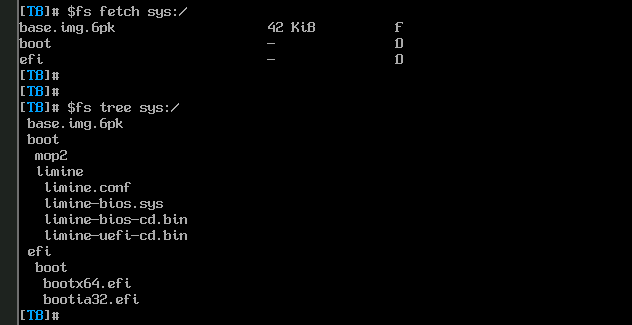

Why do I even need FAT in MOP2?

I need it, because Limine (the bootloader) uses FAT16/32 (depending on what the user picks) to store the kernel image, resource files and the bootloader binary itself. It’d be nice to be able to view all of these files and manage them, to maybe in the future for eg. update the kernel image from the system itself (self-hosting, hello?).

Fruits of labour

Here are some screenshots ;).

MBus - in-kernel messaging system

12 November 2025

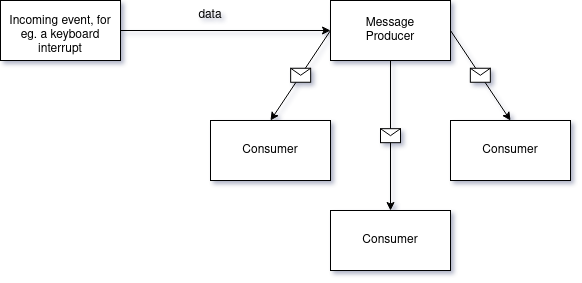

In this article I would like to present to you MBus - a kernel-space messaging IPC mechanism for

the MOP2 operating system.

One-to-many messaging

MBus is a one-to-many messaging system. This means that there’s one sender/publisher and many readers/subscribers. Think of a YouTube channel - a person posts a video and their subscribers get a push notification that there’s content to consume.

User-space API

This is the user-space API for MBus. The application can create a message bus for objmax

messages of objsize. Message buses are indentified via a global string ID, for eg. the PS/2

keyboard driver uses ID "ps2kb".

ipc_mbusattch and ipc_mbusdttch are used for attaching/detattching a consumer to/from the

message bus.

int32_t ipc_mbusmake(char *name, size_t objsize, size_t objmax);

int32_t ipc_mbusdelete(char *name);

int32_t ipc_mbuspublish(char *name, const uint8_t *const buffer);

int32_t ipc_mbusconsume(char *name, uint8_t *const buffer);

int32_t ipc_mbusattch(char *name);

int32_t ipc_mbusdttch(char *name);Usage

The usage of MBus can be found for eg. inside of TB - the MOP2’s shell:

if (CONFIG.mode == MODE_INTERACTIVE) {

ipc_mbusattch("ps2kb");

do_mode_interactive();

// ... // ...

int32_t read = ipc_mbusconsume("ps2kb", &b);

if (read > 0) {

switch (b) {

case C('C'):

case 0xE9:

uprintf("\n");

goto begin;

break;

case C('L'):

uprintf(ANSIQ_CUR_SET(0, 0));

uprintf(ANSIQ_SCR_CLR_ALL);

goto begin;

break;

}

// ...Previously reading the keyboard was done in a quite ugly manner via specialized functions of the

ps2kbdev device object (DEV_PS2KBDEV_ATTCHCONS and DEV_PS2KBDEV_READCH). It was a one big

hack, but the MBus API has turned out quite nicely ;).

With the new MBus API, the PS/2 keyboard driver becomes way cleaner than before (you can dig through the commit history…).

// ...

IpcMBus *PS2KB_MBUS;

void ps2kbdev_intr(void) {

int32_t c = ps2kb_intr();

if (c >= 0) {

uint8_t b = c;

ipc_mbuspublish("ps2kb", &b);

}

}

void ps2kbdev_init(void) {

intr_attchhandler(&ps2kbdev_intr, INTR_IRQBASE+1);

Dev *ps2kbdev;

HSHTB_ALLOC(DEVTABLE.devs, ident, "ps2kbdev", ps2kbdev);

spinlock_init(&ps2kbdev->spinlock);

PS2KB_MBUS = ipc_mbusmake("ps2kb", 1, 0x100);

}The messaging logic is ~20 lines of code now.

The tricky part

The trickiest part to figure out while implementing MBus was to implement

cleaning up dangling/dead consumers. In the current model, a message bus

doesn’t really know if a consumer has died without explicitly detattching

itself from the bus. This is solved by going through each message bus and

it’s corresponding consumers and deleting the ones that aren’t in the list

of currently running processes. This operation is ran every cycle of the

scheduler - you could say it’s a form of garbage collection. All of this

is implemented inside ipc_mbustick:

void ipc_mbustick(void) {

spinlock_acquire(&IPC_MBUSES.spinlock);

// Go through all message buses

for (size_t i = 0; i < LEN(IPC_MBUSES.mbuses); i++) {

IpcMBus *mbus = &IPC_MBUSES.mbuses[i];

// Skip unused slots

if (mbus->_hshtbstate != HSHTB_TAKEN) {

continue;

}

IpcMBusCons *cons, *constmp;

spinlock_acquire(&mbus->spinlock);

// Go through every consumer of this message bus

LL_FOREACH_SAFE(mbus->consumers, cons, constmp) {

spinlock_acquire(&PROCS.spinlock);

Proc *proc = NULL;

LL_FINDPROP(PROCS.procs, proc, pid, cons->pid);

spinlock_release(&PROCS.spinlock);

// If not on the list of processes, purge!

if (proc == NULL) {

LL_REMOVE(mbus->consumers, cons);

dlfree(cons->rbuf.buffer);

dlfree(cons);

}

}

spinlock_release(&mbus->spinlock);

}

spinlock_release(&IPC_MBUSES.spinlock);

}As you can see it’s a quite heavy operation and thus not ideal - but still way ahead of what we had before. I guess the next step would be to figure out a way to optimize this further, although the system doesn’t seem to take a noticable hit in performance (maybe do some benchmarks in the future?).

TB shell scripting for MOP2

08 November 2025

This post is about TB (ToolBox) - the shell interpreter for MOP2 operating system.

Invoking applications

Applications are invoked by providing an absolute path to the binary executable and the list of

arguments. In MOP2 paths must be formatted as MOUNTPOINT:/path/to/my/file. All paths are absolute

and MOP2 doesn’t support relative paths (there’s no concept of a CWD or current working directory).

base:/bin/pctl lsTyping out the entire path might get tiresome. Imagine typing MOUNTPOINT:/path/to/app arg more args

every time you want to call an app. This is what TB aliases/macros are for. They make the user type

less ;).

$pctl lsNow that’s way better!

Creating new aliases

To create an alias we can type

mkalias pctl base:/bin/pctlAnd then we can use our $pctl!

But there’s another issue - we have to write aliases for every application, which isn’t better than

us typing out the entire path. Luckliy, there’s a solution for this. TB has two useful functions

that can help us solve this - eachfile and mkaliasbn.

eachfile takes a directory, an ignore list and a command, which is run for every entry in the said

directory. We can also access the current directory entry via special symbol called &EF-ELEM.

In base/scripts/rc.tb we can see the full example in action.

eachfile !.gitkeep base:/bin \

mkaliasbn &EF-ELEMThis script means: for each file in base:/bin (excluding .gitkeep), call mkaliasbn for the current

entry. mkaliasbn then takes the base name of a path, which is expanded by &EF-ELEM and creates

an alias. mkaliasbn just simply does mkalias <app> MP:/path/<app>.

Logging

In the UNIX shell there’s one very useful statement - set -x. set -x tells the shell to print out

executed commands. It’s useful for script debugging or in general to know what the script does (or

if it’s doing anything / not stuck). This is one thing that I hate about Windows - it shows up a

stupid dotted spinner and doesn’t tell you what it’s doing and you start wondering. Is it stuck?

Is it waiting for a drive/network/other I/O? Is it bugged? Can I turn of my PC? Will it break if I

do? The user SHOULD NOT have these kinds of questions. That’s why I believe that set -x is very

important.

I wanted to have something similar in TB, so I’ve added a setlogcmds function. It takes yes or

no as an argument to enable/disable logging. It can be invoked like so:

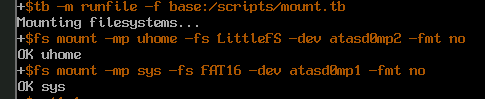

setlogcmds yesNow the user will see printed statements, for eg. during the system start up:

this is an init script!

+$tb -m runfile -f base:/scripts/mount.tb

Mounting filesystems...

+$fs mount -mp uhome -fs LittleFS -dev atasd-ch0-M-part2 -fmt no

OK uhomeString stack and subshells

In UNIX shell, it’s common to get the output of an application, store it into a variable and then pass that variable around to other apps. For eg:

# Use of a subshell

MYVAR=$(cat file.txt)

echo $MYVAR | myapp # or something...In TB, I’ve decided to go with a stack, since I find it easier to implement than a variable hashmap. A stack can be implemented using any dynamic list BTW.

The stack in TB is manipulated via stackpush and stackpop functions. We can stackpush a string

using stackpush <my string> and then stackpop it to remove it. We can also access the top of

the stack via $stack. It’s a special magic alias, which expands to the string that is at the top.

An example of stack usage would be:

stackpush 'hello world string!'

print $stack

stackpopThe do function

The do function does what a subshell does in UNIX shell. We can do a command an then have it’s

output placed at the top of the stack. An example of this would be:

do print 'hello world from subshell'

print $stack

stackpopIt’s a simpler, more primitive mechanism than the UNIX subshells, but it gets the job done ;).

Intro to MOP2 programming

14 October 2025

This is an introductory post into MOP2 (my-os-project2) user application programming.

All source code (kernel, userspace and other files) are available at https://git.kamkow1lair.pl/kamkow1/my-os-project2.

Let’s start by doing the most basic thing ever: quitting an application.

AMD64 assembly

.section .text

.global _start

_start: // our application's entry point

movq $17, %rax // select proc_kill() syscall

movq $-1, %rdi // -1 means "self", so we don't need to call proc_getpid()

int $0x80 // perform the syscall

// We are dead!!As you can see, even though we’re on AMD64, we use int $0x80 to perform a syscall.

The technically correct and better way would be to implement support for syscall/sysret, but int $0x80 is

just easier to get going and requires way less setup. Maybe in the future the ABI will move towards

syscall/sysret.

int $0x80 is not ideal, because it’s a software interrupt and these come with a lot of interrupt overhead.

Intel had tried to solve this before with sysenter/sysexit, but they’ve fallen out of fasion due to complexity.

For purposes of a silly hobby OS project, int $0x80 is completely fine. We don’t need to have world’s best

performance (yet ;) ).

"Hello world" and the debugprint() syscall

Now that we have our first application, which can quit at a blazingly fast speed, let’s try to print something. For now, we’re not going to discuss IPC and pipes, because that’s a little complex.

The debugprint() syscall came about as the first syscall ever (it even has an ID of 1) and it was used for

printing way before pipes were added into the kernel. It’s still useful for debugging purposes, when we want to

literally just print a string and not go through the entire pipeline of printf-style formatting and only then

writing something to a pipe.

debugprint() in AMD64 assembly.section .data

STRING:

.string "Hello world!!!"

.section .text

.global _start

_start:

movq $1, %rax // select debugprint()

lea STRING(%rip), %rdi // load STRING

int $0x80

// quit

movq $17, %rax

movq $-1, %rdi

int $0x80Why are we using lea to load stuff? Why not movq? Because we can’t…

We can’t just movq, because the kernel doesn’t support relocatable code - everything is loaded at a fixed

address in a process' address space. Because of this, we have to address everything relatively to %rip

(the instruction pointer). We’re essentially writing position independent code (PIC) by hand. This is what

the -fPIC GCC flag does, BTW.

Getting into C and some bits of ulib

Now that we’ve gone overm how to write some (very) basic programs in assembly, let’s try to untangle, how we get

into C code and understand some portions of ulib - the userspace programming library.

This code snippet should be understandable by now: ._start.S

.extern _premain

.global _start

_start:

call _premainHere _premain() is a C startup function that gets executed before running main(). _premain() is also

responsible for quitting the application.

// Headers skipped.

extern void main(void);

extern uint8_t _bss_start[];

extern uint8_t _bss_end[];

void clearbss(void) {

uint8_t *p = _bss_start;

while (p < _bss_end) {

*p++ = 0;

}

}

#define MAX_ARGS 25

static char *_args[MAX_ARGS];

size_t _argslen;

char **args(void) {

return (char **)_args;

}

size_t argslen(void) {

return _argslen;

}

// ulib initialization goes here

void _premain(void) {

clearbss();

for (size_t i = 0; i < ARRLEN(_args); i++) {

_args[i] = umalloc(PROC_ARG_MAX);

}

proc_argv(-1, &_argslen, _args, MAX_ARGS);

main();

proc_kill(proc_getpid());

}First, in order to load our C application without UB from the get go, we need to clear the BSS section of an

ELF file (which MOP2 uses as it’s executable format). We use _bss_start and _bss_end symbols for that, which

come from a linker script defined for user apps:

ENTRY(_start)

SECTIONS {

. = 0x400000;

.text ALIGN(4K):

{

*(.text .text*)

}

.rodata (READONLY): ALIGN(4K)

{

*(.rodata .rodata*)

}

.data ALIGN(4K):

{

*(.data .data*)

}

.bss ALIGN(4K):

{

_bss_start = .;

*(.bss .bss*)

. = ALIGN(4K);

_bss_end = .;

}

}After that, we need to collect our application’s commandline arguments (like argc and argv in UNIX-derived

systems). To do that we use a proc_argv() syscall, which fills out a preallocated memory buffer with. The main

limitation of this approach is that the caller must ensure that enough space withing the buffer was allocated.

25 arguments is enough for pretty much all appliations on this system, but this is something that may be a little

problematic in the future.

After we’ve exited from main(), we just gracefully exit the application.

"Hello world" but from C this time

Now we can program our applications the "normal"/"human" way. We’ve gone over printing in assembly using the

debugprint() syscall, so let’s now try to use it from C. We’ll also try to do some more advanced printing

with (spoiler) uprintf().

debugprint() from C// Import `ulib`

#include <ulib.h>

void main(void) {

debugprint("hello world");

}That’s it! We’ve just printed "hello world" to the terminal! How awesome is that?

uprintf() and formatted printing#include <ulib.h>

void main(void) {

uprintf("Hello world %d %s %02X\n", 123, "this is a string literal", 0xBE);

}uprintf() is provided by Eyal Rozenberg (eyalroz), which originates from Macro Paland’s printf. This printf

library is super easily portable and doesn’t require much in terms of standard C functions and headers. My main

nitpick and a dealbreaker with other libraries was that they advertise themsevles as "freestanding" or "made for

embedded" or something along those lines, but in reality they need so much of the C standard library, that you

migh as well link with musl or glibc and use printf from there. And generally speaking, this is an issue with

quite a bit of "freestanding" libraries that you can find online ;(.

Printf rant over…

Error codes in MOP2 - a small anecdote

You might’ve noticed is that main() looks a little different from standard C main(). There’s

no return/error code, because MOP2 simply does not implement such feature. This is because MOP2 doesn’t follow the

UNIX philosophy.

The UNIX workflow consists of combining many small/tiny programs into a one big commandline, which transforms text into some more text. For eg.:

cat /proc/meminfo | awk 'NR==20 {print $1}' | rev | cut -c 2- | revPersonally, I dislike this type of workflow. I prefer to have a few programs that perform tasks groupped by topic,

so for eg. in MOP2, we have $fs for working with the filesystem or $pctl for working with processes. When we

approach things the MOP2 way, it turns out error codes are kind of useless (or at least they wouldn’t get much

use), since we don’t need to connect many programs together to get something done.

Printing under the hood - intro to pipes

Let’s take a look into what calling uprintf() actually does to print the characters post formatting. The printf

library requires the user to define a putchar_() function, which is used to render a single character.

Personally, I think that this way of printing text is inefficient and it would be better to output and entire

buffer of memory, but oh well.

#include <stdint.h>

#include <system/system.h>

#include <printf/printf.h>

void putchar_(char c) {

ipc_pipewrite(-1, 0, (uint8_t *const)&c, 1);

}To output a single character we write it into a pipe. -1 means that the pipe belongs to the calling process, 0 is an ID into a table of process' pipes - and 0 means percisely the output pipe. In UNIX, the standard pipes are numbered as 0 = stdin, 1 = stdout and 2 = stderr. In MOP2 there’s no stderr, everything the application outputs goes into the out pipe (0), so we can just drop that entirely. We’re left with stdin/in pipe and stdout/out pipe, but I’ve decided to swap them around, because the out pipe is used more frequently and it made sense to get it working first and only then worry about getting input.

Pipes

MOP2 pipes are a lot like UNIX pipes - they’re a bidirectional stream of data, but there’s slight difference in the interface. Let’s take a look at what ulib defines:

int32_t ipc_piperead(PID_t pid, uint64_t pipenum, uint8_t *const buffer, size_t len);

int32_t ipc_pipewrite(PID_t pid, uint64_t pipenum, const uint8_t *buffer, size_t len);

int32_t ipc_pipemake(uint64_t pipenum);

int32_t ipc_pipedelete(uint64_t pipenum);

int32_t ipc_pipeconnect(PID_t pid1, uint64_t pipenum1, PID_t pid2, uint64_t pipenum2);In UNIX you have 2 processes working with a single pipe, but in MOP2, a pipe is exposed to the outside world and anyone can read and write to it, which explains why these calls require a PID to be provided (indicates the owner of the pipe).

#include <stddef.h>

#include <stdint.h>

#include <ulib.h>

void main(void) {

PID_t pid = proc_getpid();

#define INPUT_LINE_MAX 1024

for (;;) {

char buffer[INPUT_LINE_MAX];

string_memset(buffer, 0, sizeof(buffer));

int32_t nrd = ipc_piperead(pid, 1, (uint8_t *const)buffer, sizeof(buffer) - 1);

if (nrd > 0) {

uprintf("Got something: %s\n", buffer);

}

}

}ipc_pipewrite() is a little boring, so let’s not go over it. Creating, deleting and connecting pipes is where

things get interesting.

A common issue, I’ve encountered, while programming in userspace for MOP2 is that I’d want to spawn some external

application and collect it’s output, for eg. into an ulib StringBuffer or some other akin structure. The

obvious thing to do would be to (since everything is polling-based) spawn an application, poll it’s state (not

PROC_DEAD) and while polling, read it’s out pipe (0) and save it into a stringbuffer. The code to do this would

look something like this:

#include <stddef.h>

#include <stdint.h>

#include <ulib.h>

void main(void) {

StringBuffer outsbuf;

stringbuffer_init(&outsbuf);

char *appargs = { "-saystring", "hello world" };

int32_t myapp = proc_spawn("base:/bin/myapp", appargs, ARRLEN(appargs));

proc_run(myapp);

// 4 == PROC_DEAD

while (proc_pollstate(myapp) != 4) {

int32_t r;

char buf[100];

string_memset(buf, 0, sizeof(buf));

r = ipc_piperead(myapp, 0, (uint8_t *const)buf, sizeof(buf) - 1);

if (r > 0) {

stringbuffer_appendcstr(&outsbuf, buf);

}

}

// print entire output

uprintf("%.*s\n", (int)outsbuf.count, outsbuf.data);

stringbuffer_free(&outsbuf);

}Can you spot the BIG BUG? What if the application dies before we manage to read data from the pipe, taking the pipe down with itself? We’re then stuck in this weird state of having incomplete data and the app being reported as dead by proc_pollstate.

This can be easily solved by changing the lifetime of the pipe we’re working with. The parent process shall allocate a pipe, connect it to it’s child process and make it so that a child is writing into a pipe managed by it’s parent.

#include <stddef.h>

#include <stdint.h>

#include <ulib.h>

void main(void) {

PID_t pid = proc_getpid();

StringBuffer outsbuf;

stringbuffer_init(&outsbuf);

char *appargs = { "-saystring", "hello world" };

int32_t myapp = proc_spawn("base:/bin/myapp", appargs, ARRLEN(appargs));

// take a free pipe slot. 0 and 1 are already taken by default

ipc_pipemake(10);

// connect pipes

// myapp's out (0) pipe --> pid's 10th pipe

ipc_pipeconnect(myapp, 0, pid, 10);

proc_run(myapp);

// 4 == PROC_DEAD

while (proc_pollstate(myapp) != 4) {

int32_t r;

char buf[100];

string_memset(buf, 0, sizeof(buf));

r = ipc_piperead(myapp, 0, (uint8_t *const)buf, sizeof(buf) - 1);

if (r > 0) {

stringbuffer_appendcstr(&outsbuf, buf);

}

}

// print entire output

uprintf("%.*s\n", (int)outsbuf.count, outsbuf.data);

ipc_pipedelete(10);

stringbuffer_free(&outsbuf);

}Now, since the parent is managing the pipe and it outlives the child, everything is safe.

Hello World!

09 September 2025

This is a hello world post!

#include <stdio.h>

int main(void) {

printf("Hello World!\n");

return 0;

}Enjoy the blog! More posts are coming in the near future!

Older posts are available in the archive.