#include <threads.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

thread_local int counter = 0;

int thread_func(void *arg) {

int id = *(int*)arg;

counter++; // Each thread increments its own copy

printf("Thread %d: counter = %d\n", id, counter);

return 0;

}

int main() {

thrd_t threads[4];

int ids[4] = {1, 2, 3, 4};

for (int i = 0; i < 4; i++) {

thrd_create(&threads[i], thread_func, &ids[i]);

}

for (int i = 0; i < 4; i++) {

thrd_join(threads[i], NULL);

}

printf("Main thread counter: %d\n", counter); // Main's own copy

return 0;

}Implementing TLS (Thread Local storage) for x86_64

31 January 2026

In this article I’d like to explore the implementation details of thread local storage on x86_64/amd64 for my operating system with compliance to System V ABI.

full code is as always at: https://git.kamkow1lair.pl/kamkow1/MOP3

Preface

We’re going to implement the bare working minimum of the ABI, just enough to make thread

keyword work in Clang and GCC. The spec is more complicated than that. We’re going to implement static

TLS (there’s also dynamic TLS, you can look up tls_get_addr if you’re interested in going further).

Also I’d like to share this article as a very useful resource regarding the TLS: https://maskray.me/blog/2021-02-14-all-about-thread-local-storage. It’s more generally about TLS, but made for a great learning resource for me and I really recommend you read it too.

Other resources:

-

Spec reference: https://uclibc.org/docs/tls.pdf

-

OSDev Wiki: https://wiki.osdev.org/Thread_Local_Storage

What is thread local storage?

Thread local storage is a type of storage in a multitasked application, where each task has it’s own copy of it, distinct from other tasks.

Although the application is accessing and modifying a global variable, it’s actually different memories being used under the hood. Each thread has it’s own copy to work with.

What is thread_local? In the pre-C23 world it’s a macro, which expands to the _Thread_local keyword, which

is the same as compiler specific __thread in GCC and Clang.

Reverse engineering

We’re going to learn how the TLS works via reverse engineering. We need to understand it, before getting to Implementing it ourselves. Let’s look at the disassembly first, generated by Clang 21.1.0 on https://godbolt.org.

I’ve added some comments here, so everything is nice and easy to read.

/* int thread_func(void *arg) */

thread_func:

/* Push new stack frame */

push rbp

mov rbp, rsp

mov qword ptr [rbp - 8], rdi /* store arg on the stack frame */

/* Read the ID value */

/* int id = *(int*)arg; */

mov rax, qword ptr [rbp - 8]

mov eax, dword ptr [rax]

mov dword ptr [rbp - 12], eax

/* counter++; */

mov rax, qword ptr fs:[0] /* ?????????? */

lea rax, [rax + counter@TPOFF]

mov ecx, dword ptr [rax]

add ecx, 1 /* do the ++ */

mov dword ptr [rax], ecx

/* return 0; */

xor eax, eax

pop rbp

ret

/* The rest is irrelevant here... */

counter:

.long 0What is fs:[0] (also written commonly as %fs:0 in GNU syntax)?

We’re going to refer to fs as %fs (GNU syntax), because that’s how I write my assembly, but you can look

up the analogous syntax for you assembler (like nasm or fasm).

x86 segmentation

%fs is an x86 segment register. There are also other segment registers:

-

%cscode segment -

%dsdata segment -

%ssstack segment -

%esextra segment -

%fs,%gsgeneral segments

Real mode (16 bit)

x86_64 (yes, a 64 bit CPU) boots up first in 16 bit mode or the "real mode". In real mode we only have 16 bit registers, so one might think that we can address only up to 64K of memory. Segmentation let’s us use more memory, because it changes the logical addressing scheme. Instead of pointing to a specific byte in memory, we an point to a block of memory and displace from the base of it to get the byte - and thus we can address more than 64K. Early x86 CPUs (like the OG Intel 8086) could address up to 1MB.

This explains the %fs:0 syntax. We have a %fs base and a 0 displacement.

A good explaination can be also found on the OSDev wiki: https://wiki.osdev.org/Segmentation.

Also reading the GDT article will come in handy: https://wiki.osdev.org/Global_Descriptor_Table. From now on

I will assume we’re already working with 64 bit GDT and we’re going to skip the 32 bit mode entirely in this

article.

Long mode (64 bit)

Real mode uses 16 bit addresses as the segment base, so analogously 64 bit segmentation will use 64 bit addresses.

Segment registers are different

Segment registers are not like your typical %rax or %rcx - at least some. You can freely write to %ds,

%ss, %es and that’s it! %cs, %fs, %gs are special in that they cannot be written to manually.

%cs can be reloaded by for example lretq instruction, %fs and %gs require writing to an MSR

(will explain in a bit).

Detour about MSRs

MSR mean Model-Specific Register. Intel basically wanted to add unstable features and didn’t want to clutter up their architecture with experimental slop. Some of the MSRs were useful enough that they made it into future Intel CPUs and stayed with us. Generaly speaking, MSRs control OS-related stuff about the CPU.

MSRs are used with the rdmsr/wrmsr instructions. The scheme is like so:

movl NUMBER_OF_MSR, %ecx

movl VALUE_BITS_LOW, %eax

movl VALUE_BITS_HIGH, %edx

wrmsr

movl NUMBER_OF_MSR, %ecx

rdmsr

/* now %eax contains high bits and %edx low bits. These two shall be concatinated into a 64 bit value */%fs and MSRs

I’ve mentioned previously that the %fs and %gs registers can be written to by writing to an MSR - but which one?

The MSR we care about is called (in the Intel manual) IA32_FS_BASE. To address the confusion early on I’ll say

that some people call it slightly differently, for eg. in the Xen hypervisor code it’s called MSR_FS_BASE. My

kernel takes the definition header from Xen, so that’s why I will use Xen’s naming scheme, but IA32_FS_BASE

would be the official name.

Looking at the file kernel/amd64/msr-index.h we can see a juicy #define:

#define MSR_FS_BASE _AC (0xc0000100, U) /* 64bit FS base */The magic MSR number is 0xc0000100. Here’s how I’m using it:

void do_sched (struct proc* proc, spin_lock_t* cpu_lock, spin_lock_ctx_t* ctxcpu) {

spin_lock_ctx_t ctxpr;

spin_lock (&proc->lock, &ctxpr);

thiscpu->tss.rsp0 = proc->pdata.kernel_stack; /* set TSS kernel stack */

thiscpu->syscall_kernel_stack = proc->pdata.kernel_stack; /* set syscall entry stack */

amd64_wrmsr (MSR_FS_BASE, proc->pdata.fs_base); /* switch to proc's fs base */

spin_unlock (&proc->lock, &ctxpr);

spin_unlock (cpu_lock, ctxcpu);

amd64_do_sched ((void*)&proc->pdata.regs, (void*)proc->procgroup->pd.cr3_paddr);

}The MSR helpers are written like so:

/// Read a model-specific register

uint64_t amd64_rdmsr (uint32_t msr) {

uint32_t low, high;

__asm__ volatile ("rdmsr" : "=a"(low), "=d"(high) : "c"(msr));

return ((uint64_t)high << 32 | (uint64_t)low);

}

/// Write a model-specific register

void amd64_wrmsr (uint32_t msr, uint64_t value) {

uint32_t low = (uint32_t)(value & 0xFFFFFFFF);

uint32_t high = (uint32_t)(value >> 32);

__asm__ volatile ("wrmsr" ::"c"(msr), "a"(low), "d"(high));

}What we do is we swap out base value of %fs for each process and every process has it’s own TLS!

When processes are switched, the new MSR_FS_BASE is written.

So what is %fs:0 again?

We’ve managed to establish what %fs is, but what %fs:0 is?

The authors of System V TLS ABI for x86_64 were quite smart. %fs CANNOT be accessed on it’s own, sort of. We

can’t use it like a regular pointer to the TLS. We can only use segment registers with a displacement.

So when we can’t use %fs, we can use %fs:0! %fs points to the TLS + 8 byte pointer back to itself, so then

%fs:0 can become a pointer to the real TLS memory block.

Also, the TLS variable offsets are negative!

The TLS memory:

Var 1 Var 2 Var 3 Var 4 .... The pointer

+-------------------------------------------------------------------------------+

| | | | | | | | | | <---+

+-------------------------------------------------------------------------------+ |

|

^ |

| |

TLS (fs base) |

|

%fs:0 --------------+If this is too difficult to grasp (don’t worry, I’ve spent days banging by head against a wall mysekf), I’ll show you now the code, which handles the TLS in a bit. Now we’re going to take another detour to discuss how the TLS looks like from the perspective of the ELF file format.

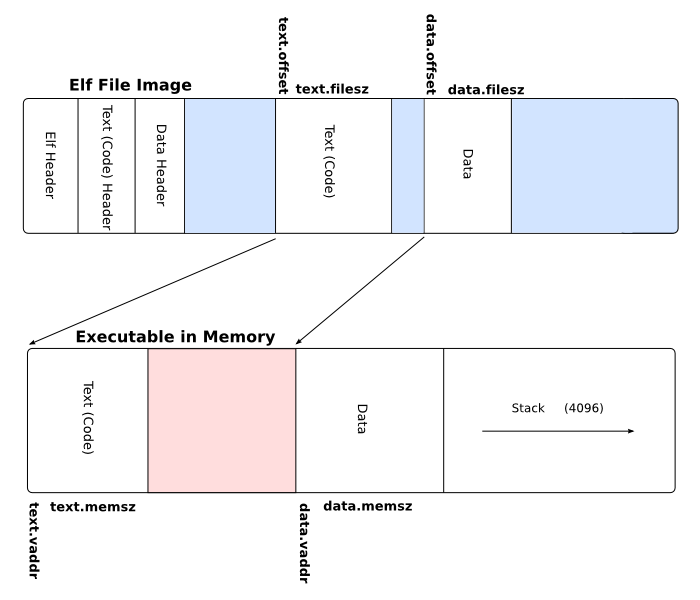

TLS and ELF relationship

I’m not going to go out of my way to explain the ELF format entirely - it’s out of scope for today, but I’ll link a useful article here: https://wiki.osdev.org/ELF. It’s a great read on the basics of the ELF format.

ELF has the so-called "sections". A section is a piece of data that makes up the final executable. A section can

be .text where your executable code resides or .rodata where your read-only data sits (like string literals).

ELF also has a special TLS section. This may seem confusing, since why would ELF store some sort of TLS, when each task must have it’s own? The TLS section is actually a template/"meta" section. It’s not the actual TLS, but rather a template of how should the TLS be contructed.

For example:

__thread int a = 123;

void my_thread (void) {

printf ("a = %d\n", a);

a = 456;

printf ("a = %d\n", a);

}The first printf will display 123, because the TLS template says that a shall have initial value of 123, but

then the thread is free to modify it’s own version. It just starts out with what is provided by the ELF file.

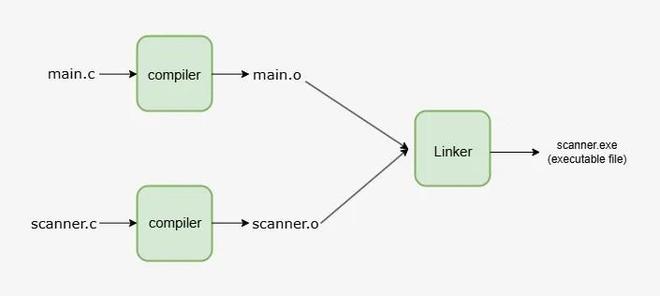

Linking the user application

An ELF application has to be linked after we’ve compiled all the necessary object files.

To get the exact ELF layout we need (remember, we’re making our own OS), we can use a linker script.

OUTPUT_FORMAT(elf64-x86-64)

ENTRY(_start)

PHDRS {

text PT_LOAD;

rodata PT_LOAD;

data PT_LOAD;

bss PT_LOAD;

tls PT_TLS; /* <------ !!!! */

}

SECTIONS {

. = 0x0000500000000000;

/* The executable code instructions */

.text : {

*(.text .text.*)

*(.ltext .ltext.*)

} :text

. = ALIGN(0x1000);

/* Read-only data */

.rodata : {

*(.rodata .rodata.*)

} :rodata

. = ALIGN(0x1000);

/* initialized data */

.data : {

*(.data .data.*)

*(.ldata .ldata.*)

} :data

. = ALIGN(0x1000);

__bss_start = .;

/* uninitialized data */

.bss : {

*(.bss .bss.*)

*(.lbss .lbss.*)

} :bss

__bss_end = .;

. = ALIGN(0x1000);

__tdata_start = .;

/* initialized TLS data */

.tdata : {

*(.tdata .tdata.*)

} :tls /* <------ !!!! */

__tdata_end = .;

__tbss_start = .;

/* uninitialized TLS data */

.tbss : {

*(.tbss .tbss.*)

} :tls /* <------ !!!! */

__tbss_end = .;

__tls_size = __tbss_end - __tdata_start;

/DISCARD/ : {

*(.eh_frame*)

*(.note .note.*)

}

}PT_TLS is the "program header" type - in this case we say that we want this part of the executable to be of

TLS type. This will help our OS' loader distinguish between different parts of the app and how should it act upon

them.

Also note that we mark .tdata and .tbss both as :tls. This just tells the linker to merge those sections

together into a tls section (which we mark as PT_TLS).

Loader

Now let’s take a look inside the ELF loader:

case PT_TLS: {

#if defined(__x86_64__)

if (phdr->p_memsz > 0) {

/* What is the aligment we need to use? */

size_t tls_align = phdr->p_align ? phdr->p_align : sizeof (uintptr_t);

/* Size of the TLS memory block (variables go here) */

size_t tls_size = align_up (phdr->p_memsz, tls_align);

/* Size needed - TLS block size + 8 bytes (64 bits) for back pointer */

size_t tls_total_needed = tls_size + sizeof (uintptr_t);

/* amount of pages to allocate */

size_t blks = div_align_up (tls_total_needed, PAGE_SIZE);

/* Initialize TLS template in the procgroup. This will be copied into individual TLSes */

proc->procgroup->tls.tls_tmpl_pages = blks;

proc->procgroup->tls.tls_tmpl_size = tls_size;

proc->procgroup->tls.tls_tmpl_total_size = tls_total_needed;

/* malloc () and zero out */

proc->procgroup->tls.tls_tmpl = malloc (blks * PAGE_SIZE);

memset (proc->procgroup->tls.tls_tmpl, 0, blks * PAGE_SIZE);

/* copy initialized stuff */

memcpy (proc->procgroup->tls.tls_tmpl, (void*)((uintptr_t)elf + phdr->p_offset),

phdr->p_filesz);

proc_init_tls (proc);

}

#endif

} break;void proc_init_tls (struct proc* proc) {

struct limine_hhdm_response* hhdm = limine_hhdm_request.response;

/* This application doesn't use TLS */

if (proc->procgroup->tls.tls_tmpl == NULL)

return;

size_t tls_size = proc->procgroup->tls.tls_tmpl_size;

size_t pages = proc->procgroup->tls.tls_tmpl_pages;

uintptr_t tls_paddr;

uint32_t flags = MM_PG_USER | MM_PG_PRESENT | MM_PG_RW;

/* allocate a new TLS memory space and map it into the procgroup's address space */

uintptr_t tls_vaddr = procgroup_map (proc->procgroup, 0, pages, flags, &tls_paddr);

uintptr_t k_tls_addr = (uintptr_t)hhdm->offset + tls_paddr;

/* zero and copy the template contents */

memset ((void*)k_tls_addr, 0, pages * PAGE_SIZE);

memcpy ((void*)k_tls_addr, (void*)proc->procgroup->tls.tls_tmpl, tls_size);

/* kernel address and user address + size will point to the tls pointer */

uintptr_t ktcb = k_tls_addr + tls_size;

uintptr_t utcb = tls_vaddr + tls_size;

/* write the pointer value, which makes the TLS point to itself */

*(uintptr_t*)ktcb = utcb;

/* store as fs_base for switching during scheduling */

proc->pdata.fs_base = utcb;

/* save allocation address to later free it when not needed */

proc->pdata.tls_vaddr = tls_vaddr;

}Conclusion

And that’s it! we can use the TLS now in user apps!

#define MUTEX 2000

LOCAL volatile char letter = 'c';

void app_proc1 (void) {

letter = 'a';

for (;;) {

mutex_lock (MUTEX);

for (int i = 0; i < 3; i++)

test (letter);

mutex_unlock (MUTEX);

}

process_quit ();

}

void app_proc2 (void) {

letter = 'b';

for (;;) {

mutex_lock (MUTEX);

for (int i = 0; i < 3; i++)

test (letter);

mutex_unlock (MUTEX);

}

process_quit ();

}

void app_proc3 (void) {

letter = 'c';

for (;;) {

mutex_lock (MUTEX);

for (int i = 0; i < 3; i++)

test (letter);

mutex_unlock (MUTEX);

}

process_quit ();

}

void app_main (void) {

mutex_create (MUTEX);

letter = 'a';

process_spawn (&app_proc1, NULL);

process_spawn (&app_proc2, NULL);

process_spawn (&app_proc3, NULL);

for (;;) {

mutex_lock (MUTEX);

for (int i = 0; i < 3; i++)

test (letter);

mutex_unlock (MUTEX);

}

}My personal thoughts

This was difficult… Way too difficult to implement. When reading the spec and then trying to make it work, I’ve noticed that all this pointer/size/alignment trickery is just so we can go around the face that x86_64 doesn’t have a built-in architectural mechanism to support such thing as TLS. All you have is a bunch of free registers and it’s up to you to make something out of that. I guess ARM is better in this case, because there’s a single source of authority that produces the CPU and sets the rules to abide by.